AI Isn’t the Enemy—Ignorance Is

I do NFL analytics where I develop and use models to predict the outcome of Super Bowls, seasons, and this year I am experimenting on a week to week basis. It is about 120 hours of work per year. After completing this year's predictions, I decided to experiment by uploading the data projections and each team's schedules and asking them to do the same tasks that I did. It made so many errors that I determined it is not worth it.

ChatGPT's predictions revealed its fundamental limitation. It predicted five teams going either 17-0 or 0-17—outcomes that have never happened in NFL history. My algorithms, built on understanding how injuries, coaching changes, and division dynamics actually work, predicted the same teams in the 6-12 win range. ChatGPT was pattern-matching without context; I was analyzing actual football dynamics. By Week 9, my predictions were outperforming the AI significantly because I understood what the numbers meant, not just what they said.

The AI was pattern-matching without context; I was analyzing actual football dynamics.

Additionally, I know a data scientist that codes for major companies. He uses various AIs to code. He has to go back in and correct its errors. Using AI does not replace the ability to use mathematical analysis. AI did not make him able or unable to code. It is our knowledge within various fields that allow us to use AI more effectively and realize when it is mistaken. This pattern of an AI as a tool requiring human expertise is what many educators miss in debates about classroom AI use.

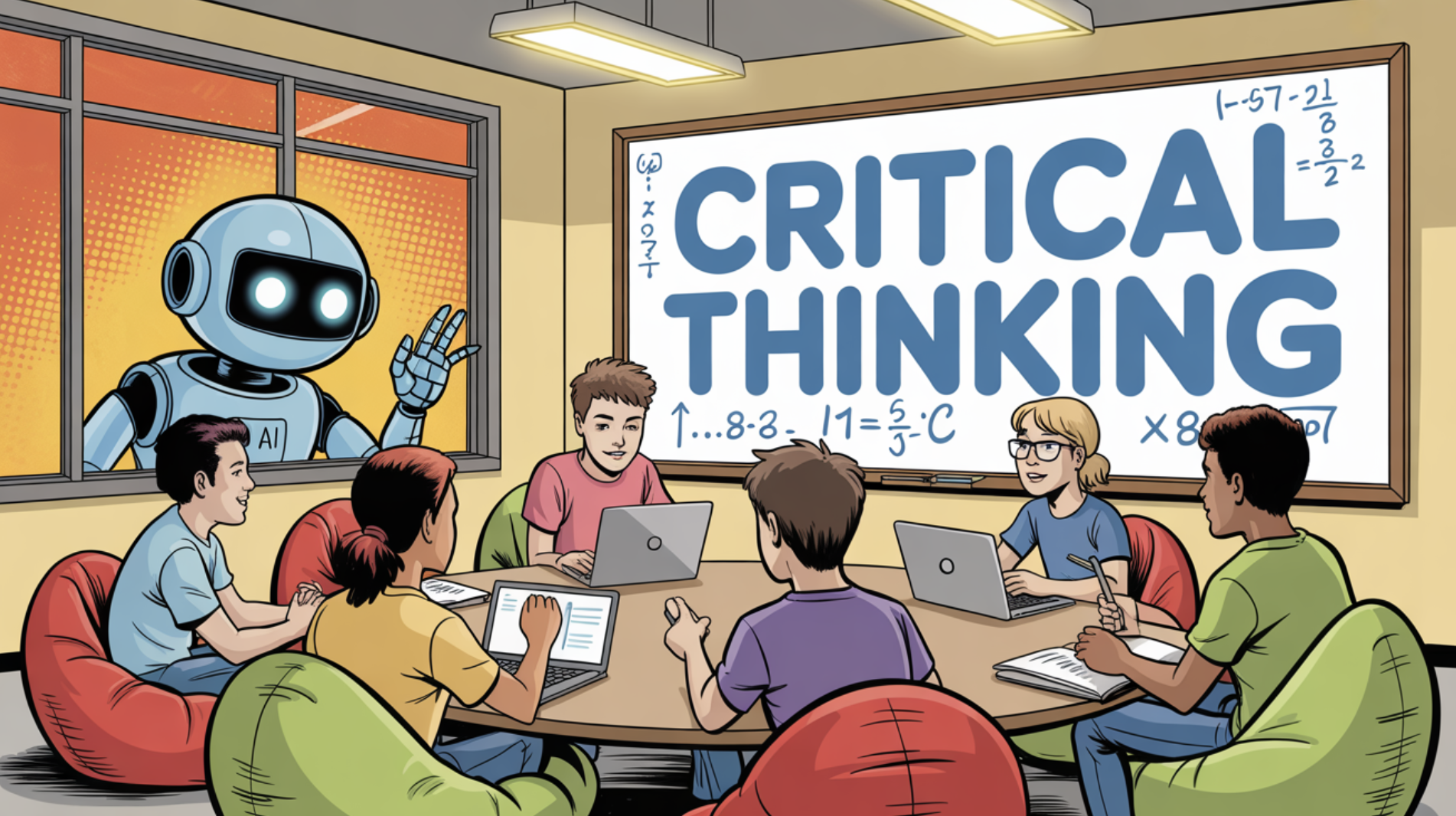

The Split Room: Bans vs. Integration

Recently, I attended a state level education meeting where one of the topics was artificial intelligence. It was an interesting dynamic as the room was split. The first group to speak focused on the challenges of AI, while the second group (of which I was a part) focused on the benefits and opportunities. The first group spoke about the efforts they have taken to ban AI and argue with parents that claim that their children did not use AI. The first group discussed how students are using AI to write their papers and essays at home. They run the essays through AI detectors and report it to the parents. Then, the parents are coming in and denying that the students are using AI.

Our group was talking about how we have embraced AI and how we are using it to benefit teachers and students. We believe that banning AI will not make it go away. Banning AI will not give your students a competitive advantage in their future.

While there are varying hypotheses regarding the purpose of public education, the majority that I have seen tend to state in wording that schools are meant to prepare students to be an economically and socially successful adult that can contribute and participate in society. That being said, policies around AI and school practices vary and in many places are a betrayal to the mission of preparing students to be a successful adult. Understanding how to use AI effectively and responsibly, not whether to use it, should be the question.

Who Succeeds with AI and Why It Matters

Last October, I became interested in learning how to use AI. I experimented with various AI tools. I ended up creating a presentation called AI Tools for Education and began using that to train K-12 teachers in my district. As I was learning AI, I heard concerns about AI inhibiting writing and communication skills. I found that there are opportunities on both ends. As I became more experience at using AI, I realized that the technology rewards certain types of communicators.

For example, prompting makes one better at a specific type of communication, which I call precision communication. I have observed, but not tested, the people that are strong at with persuasive language skills, job interviews, sales presentations, etc. have a harder time with writing prompts. Many of these people have not mastered being direct, but using emotional and figurative language, political nuance, and forms of persuasion to get around facts, evidence, and truth. They are masters of spin, but their words may not actually get to the point. That approach often makes them successful in the world, but an AI is not a human with emotions that can be persauded.

Precision communication works best for those that are direct, truthful, and can be as specific as possible. The bots reward people that provide as much detail and information as possible. As Machiavelli pointed out in The Prince, the world tends to devour those who are unfailingly direct and honest. AI, by contrast, rewards exactly these individuals.

I have observed, but not tested that students with high-functioning autism often excel at prompting because they communicate with the directness AI requires. Recent research supports this. Iannone and Giansanti's 2023 narrative review of 22 studies shows AI helping individuals with autism develop communication skills precisely because the technology rewards clarity over social performance. This raises interesting questions about which students AI might advantage or disadvantage, but the broader point remains: effective AI use requires understanding how these systems process information.

From Communication to Curriculum Design

This specificity requirement applies beyond communication and it extends to how we design learning experiences. As someone that has designed Project Based Learning (PBL) Activities since 2012, various chatbots have helped me augment ideas and help create more specific lesson plans using them. I have various ideas, but turning each one into full-fledged lessons over multiple weeks with all the subsequent materials used to take months, weeks, or days. I can now do it in much less time with the help of AI. This December, I am beginning to train teachers on how to use various AI software to create PBLs that allow various forms of multimedia. But like my NFL analytics work, this efficiency only works because I bring pedagogical expertise to the process. AI accelerates what I already know how to do.

I gave Claude AI my basic project outline and asked it to expand it into a complete unit covering specific algebra standards like building functions, geometric series, recursive sequences. The AI generated a detailed framework in minutes. It looked great at first glance. But here's where my expertise mattered: I had to verify every mathematical concept was taught in the right sequence, ensure activities were developmentally appropriate for 16-year-olds, and redesign the assessment to focus on mathematical thinking rather than just correct answers.

Someone without years of design experience might have used the AI's plan as is and created a unit that looked complete but failed to build genuine understanding. The AI accelerated my workflow, but only because I knew what to look for, what to fix, and why those changes mattered. This is what I mean by AI requiring expertise. It's a drafting tool, not a replacement for pedagogical judgment.

When AI Fails Students

Banning AI doesn't solve problems with the adoption of AI in education. Maybe we should require students to solve problems manually first, then verify with AI. Or maybe have AI disagree with their answer so they must reason which approach is correct and why. This builds the domain knowledge they need to supervise AI effectively rather than depend on it blindly.

The split room at that state education meeting represents a choice every school system is making right now. Those that develop teacher expertise in AI integration will prepare students for an AI-saturated workplace. Those that ban AI will produce graduates who learned to use it anyway, just without guidance.

Denial of a problem does not make it go away. The Internet did not disappear. The smart phone did not disappear. Social media did not disappear. There is apprehension around the usage of Artificial Intelligence in schools, classrooms, etc. Like any technology, there are those that avoid it until they cannot, early adopters, and fencesitters. Will educators develop the expertise to use it well or pretend it doesn't exist while students and others move forward without guidance?

About the Author

Michael Tofte, Jr. is a former Chief Academic Officer and current Educational Leader in Science, Technology, & Career Readiness, who has designed project-based learning curricula since 2012 and trains K-12 teachers on AI integration. He develops predictive analytics models for NFL outcomes and has been featured in Education Week, Education Dive, and the Christian Science Monitor.

References

Chalkbeat. (2023, January 5). NYC schools ban ChatGPT on district networks and devices. https://www.chalkbeat.org/newyork/2023/01/05/nyc-schools-ban-chatgpt/

Giansanti, D., & Iannone, A. (2024). Breaking barriers—The intersection of AI and assistive technology in autism care: A narrative review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 14(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14-00041

The Guardian. (2023, May 19). US schools reverse ChatGPT bans as educators see potential. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/may/19/chatgpt-school-ban-reversal

Kennedy, B., Yam, E., Kikuchi, E., Pula, I., & Fuentes, J. (2025, September 17). How Americans view AI and its impact on people and society. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2025/09/17/how-americans-view-ai-and-its-impact-on-people-and-society/

Tofte Jr., M. (2025). Chat GPT failed at using my algorithms that predict NFL season outcomes. Medium. https://medium.com/@piningforthe80s/chat-gpt-failed-at-using-my-algorithms-that-predict-nfl-season-outcomes-c7edb8a7f626

Williamson, B., & Piattoeva, N. (2023). Education governance and the rise of algorithmic systems: AI in schools. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2172389