The Neurobiology of Dyslexia and the Role of AI in Inclusive Education

In my thirteen years as an educator, and throughout my own life as a person with dyslexia, I have witnessed a recurring and painful phenomenon I call the "Output Paradox." It occurs when a student can verbally explain a complex scientific process, yet when presented with a written prompt, they produce only a few brief, detail-lacking sentences.

To an outside observer, this might appear to be a lack of effort or a deficit in intelligence. But through the lens of neuroscience, we know this isn't a cognitive failure; it is a biological bottleneck. Developmental Dyslexia (DD) is formally defined as a persistent difficulty in achieving high-level reading and writing skills, often manifesting as slow word recognition and spelling (Peterson & Pennington, 2012). Today, as Artificial Intelligence enters the classroom, we are finally finding the tools to bypass that bottleneck and allow these students' true potential to reach its full potential.

Neurobiology of Dyslexia

Reading and writing are not evolutionarily "natural" tasks. Unlike speaking, which the human brain is naturally wired for, literacy requires us to build a neural bridge between the auditory centers (which process sounds) and the visual cortex (which processes letters) (Frith & Snowling, 1983).

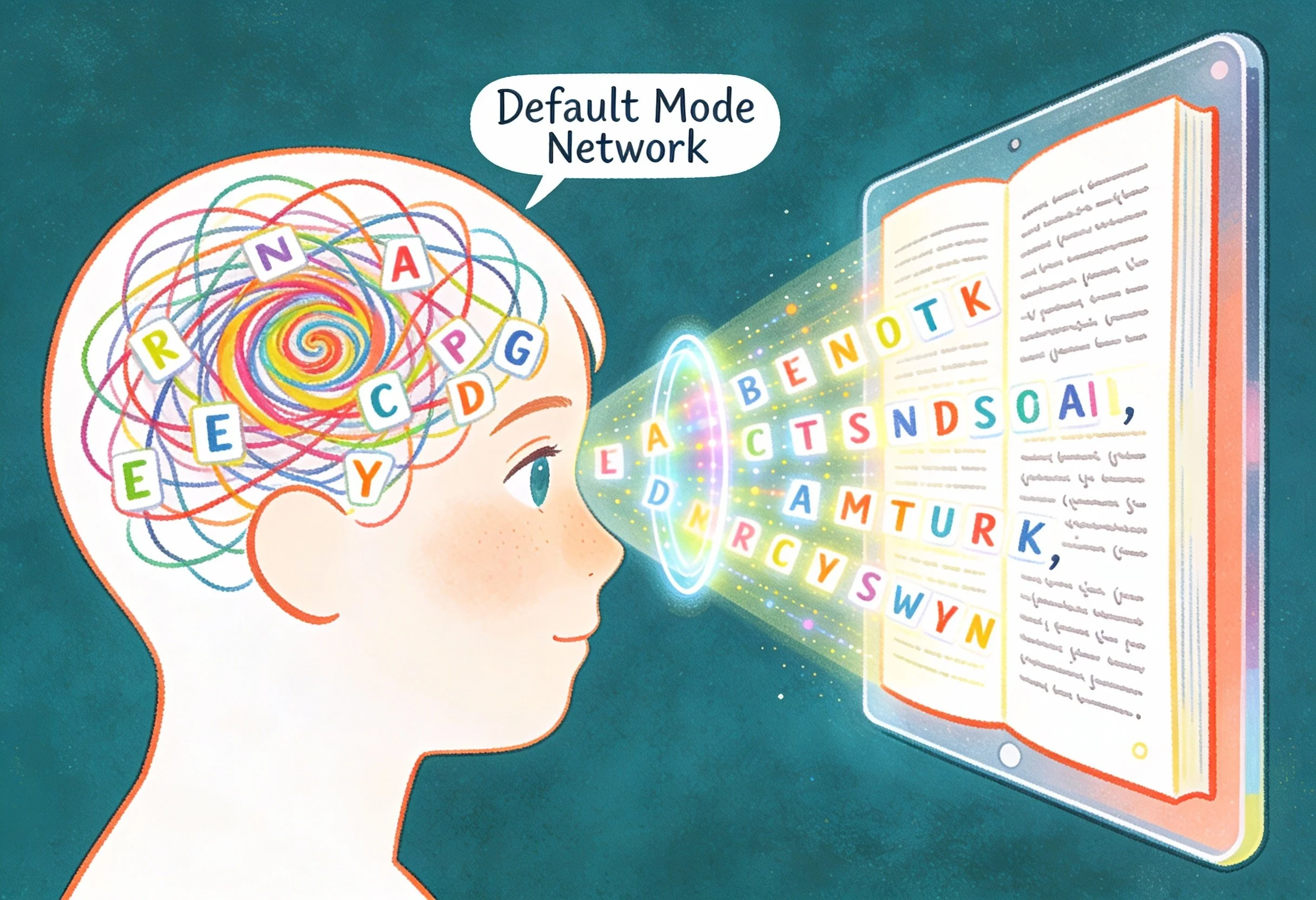

The brain has to exert immense conscious energy just to decode or encode

In a typically developing brain, this bridge becomes "automated." The brain stops focusing on individual letters and starts concentrating entirely on the meaning. In the dyslexic brain, this bridge remains under construction or functions differently. Research into the "Default Mode Network" (DMN), the part of the brain responsible for imagination and global thinking, reveals that it is often highly active in individuals with dyslexia (Taylor & Vestergaard, 2022). However, because the brain has to exert immense conscious energy just to decode or encode, a process called the automatization deficit, there is simply a lack of energy or ideas forgotten from working memory for the actual content of the writing (Taylor & Vestergaard, 2022). This is why a brilliant young scientist who is a student can struggle to write a lab report. The energy is consumed by the mechanics, leaving the ideas stranded in the mind.

One of the most profound moments in my educator's journey is the transition from trying to “fix" dyslexia to learning to navigate it. As a person with dyslexia, the most important breakthrough for me was realizing that my strengths lie in non-linguistic areas. I had to accept that reading and writing will always be challenging.

It is difficult to accept that a fundamental part of the modern world will always be a struggle, but it is also liberating. Once a student stops trying to force their brain to act like a "typical" brain, they can begin to lean into their strengths. As teachers, our role is to protect a student's dignity during this friction phase. We must help them see that their brain isn't broken; it is simply optimized for a different kind of processing.

AI as an Accessibility Tool

A fierce debate is currently raging in education regarding the academic integrity of AI tools. Many fear that AI will make students "lazy" or lead to widespread cheating. I believe we need a more nuanced perspective: AI is likely a "net negative" for the general student population, who may use it to bypass original thought. However, for the dyslexic student, AI is a "net positive" and a matter of educational equity.

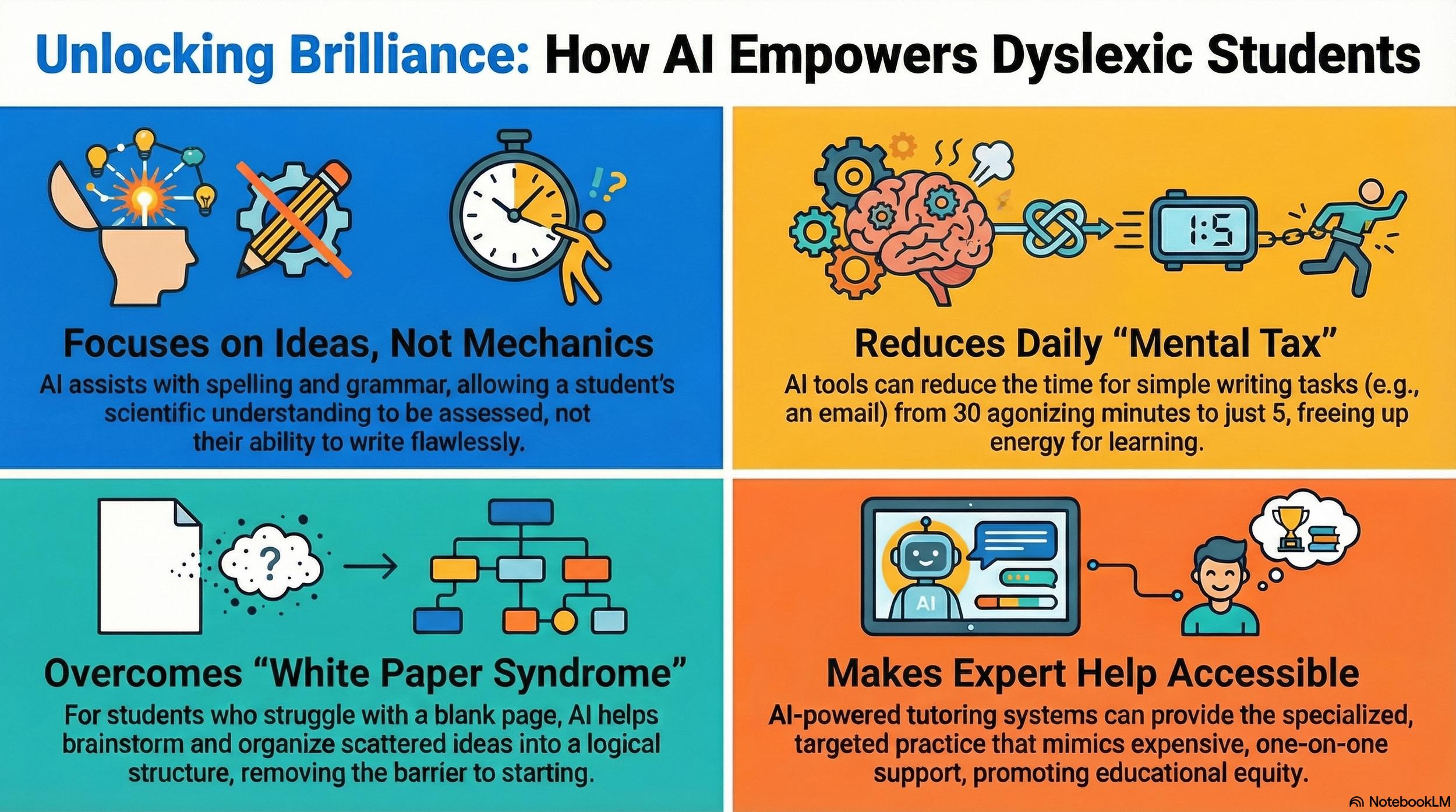

The key to this distinction lies in the academic standard being assessed. In my science classroom, when I ask students to make detailed observations of a natural phenomenon, the "standard" I am assessing is their scientific inquiry: ability to ask questions, to connect prior knowledge, to analyze patterns. I am checking to see if they can notice the subtle changes in a chemical reaction or the patterns in an ecosystem. In this context, the student's ability to spell "precipitate" correctly is irrelevant to the learning objective.

Using AI to assist with grammar and spelling is not cheating in this scenario. Just as we provide a wheelchair for a student with a physical disability to navigate the school halls, we must provide AI for the dyslexic student to navigate the linguistic halls of the curriculum. It allows them to produce the complete, detailed statements their minds are capable of without being sabotaged by their spelling.

One of the most practical ways AI transforms a dyslexic student's life is by solving "White Paper Syndrome". (Dyslexia Explored Podcast, 2023) For a person with dyslexia, a blank screen is not an opportunity; it is a wall. Starting a task requires a massive amount of activation energy.

Dyslexics may find that starting with a brainstorm or an outline of a previous essay helps them with a new assignment. AI sequencing tools are perfect for this. They allow a student to "dump" their ideas into a tool that helps them organize those thoughts into a logical order.

Consider the impact on a student's mental health. A simple task like sending a formal email to a teacher might take a dyslexic student 30 minutes of agonizing effort, checking every word, worrying about the tone, and fearing judgment. With an AI tool, that same student can get it done in 5 minutes. That 25-minute difference is a huge step forward. It reduces the "mental tax" that dyslexia imposes on every daily interaction, leaving more energy for the student actually to learn.

For decades, the "gold standard" for supporting individuals with dyslexia has been one-on-one tutoring, specifically utilizing the Orton-Gillingham (OG) approach or Wilson Reading System (WRS). OG and WRS tutors provide the multisensory, highly structured instruction that dyslexic brains need to build those missing neural bridges.

The problem is that tutoring is incredibly expensive and rare. In many parts of the world, and even in many under-resourced schools, this level of support is not available. This creates a literacy divide where only the wealthy can afford to unlock their child's potential.

AI-powered Intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) could change this. Systems like to build adaptive platforms that build a student learning model (Improving Educational Outcomes for Dyslexic Students with AI-Driven Learning | SchoolAI, 2025). It tracks where a student is struggling, perhaps it's a specific phonics rule, such as the 'oa' sound, and it provides targeted, repetitive practice that mimics the attention of a human tutor. While AI can never replace the emotional support and expertise of a teacher, it can provide the specialized drills and immediate feedback necessary for progress, making high-level support accessible to every student.

A New Era of Inclusive Education

As we look toward the future, we must be careful not to throw the "AI baby" out with the "cheating bathwater." For students with dyslexia, these tools represent the first significant technological breakthrough that levels the playing field since the word processor. We should use AI to remove the mechanical barriers that hide the brilliance of neurodivergent minds. By embracing AI assistance, we move closer to an educational system where every student, regardless of their unique brain wiring, has the opportunity to have their voice heard.

About the Author

Stephen C. Lawrence is a middle school teacher at Jakarta Intercultural School (JIS) specializing in science and math, and I also serve as a grade-level leader. He holds a Bachelor's degree in Psychology and a Master's degree in Education. Additionally, he has spent seven years in the mental health field and two years at a specialized school for Dyslexic students, where he utilized Orton-Gillingham training. Stephen is dyslexic and his experience has inspired him to incorporate neuroscience/educational research into his teaching methods, particularly for students with dyslexia.

REFERENCES

Taylor, H., & Vestergaard, M. D. (2022). Developmental Dyslexia: Disorder or Specialization in Exploration? Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.889245

Peterson, R. L., & Pennington, B. F. (2012). Developmental dyslexia. Lancet 379, 1997–2007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60198-6

Dyslexia Explored Podcast. (2023, March 17). #131 What is the Dyslexic Advantage? Find out from Authors Dr Brock and Dr Fernette Eide [Audio podcast]. Spotify.

Frith, U., & Snowling, M. (1983). Reading for Meaning and Reading for Sound in Autistic and Dyslexic Children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 1(4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835x.1983.tb00906.x

Improving Educational Outcomes for Dyslexic Students with AI-Driven Learning | SchoolAI. (2025). Schoolai.com. https://schoolai.com/blog/improving-educational-outcomes-dyslexic-students-ai-driven-learning