The Cognitive Offloading Crisis: How AI is Changing the Way Students Think and Learn.

A new Pattern in the Classroom

In recent years, I have noticed a subtle but unmistakable shift in the way many children approach learning. When faced with a challenge, whether recalling a concept, understanding a text, or solving a question, the instinctive response is no longer to think, but to search. AI tools now give instant answers with astonishing fluency, and students are learning that they do not need to struggle, retrieve, or connect ideas if technology can do it for them.

I have spent the past decade leading digital transformation in school and training teachers to integrate technology responsibly. I have become increasingly concerned about how easily children, and sometimes parents, outsource thinking. There’s an erosion of the cognitive habits that make learning possible.

This is the cognitive offloading crisis: the increasing tendency to delegate mental effort to external tools. And in the age of AI, it is accelerating.

But What is Cognitive Offloading?

Cognitive offloading is the process of reducing the brain’s workload by relying on external aids, whether notebooks, screens, shortcuts, or algorithms. In moderation, it is essential. We all use calendars, reminders, GPS, and calculators to free mental resources for higher-level thinking.

But when offloading becomes a habitual substitution for effort, it weakens the very processes that build memory, understanding, and reasoning. Technology saves time, but learning requires time. Technology reduces effort, but learning requires effort. When the balance tips too far towards technology, the brain may lose opportunities to grow.

In today’s classrooms, that balance is tipping rapidly.

How AI Amplifies This Crisis?

AI systems can now generate answers faster than a student can think through the question. For a developing mind, the temptation to skip the cognitive process is enormous. I have observed this in many forms:

Students relying on instant summaries instead of reading.

Learners using translation tools rather than attempting vocabulary recall.

Children solving maths problems by typing them into a chatbot rather than reasoning through the steps.

A shortcut that once saved a minute can now replace an entire intellectual journey.

When teachers use both Learning by Questions (LBQ) and Century Tech, something becomes very clear. LBQ requires students to type their answers. It demands retrieval, active recall, and accuracy before moving on. Students must think. They must commit to an answer. They must struggle a little.

Century Tech, on the other hand, often relies on multiple-choice questions. Many students quickly learn to guess. They do not retrieve; they eliminate. They do not generate; they click. The system can give an illusion of progress without underlying thinking. AI amplifies this tendency on an exponential scale. A shortcut that once saved a minute can now replace an entire intellectual journey.

What Neuroscience Says About Thinking and Memory

Learning is a physical process. Research by cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene, particularly in his work How We Learn, reinforces that effortful retrieval and deliberate practice strengthen neural pathways and are essential for durable learning. Every time a student retrieves information, attempts a solution, or reflects on an idea, the brain strengthens the relevant neural pathways. Dendrites grow. Synaptic connections stabilise. Myelin thickens around circuits that are repeated. These changes do not occur when answers are delivered passively.

Deep learning requires:

Struggle – those productive moments of “I need to think.”

Retrieval – recalling information without support.

Generation – producing ideas, not selecting them.

Reflection – comparing what one knows with new information.

AI may be able to support these processes, but it will never be able to replace them. When students bypass these steps, they may feel successful, but the memory traces remain fragile. They gain solutions, not understanding. Fluency, not mastery. Confidence, but not competence.

The greatest danger is raising children who appear knowledgeable, but have not actually learned.

Practical Strategies for Reducing Cognitive Offloading in the Classroom

The solution to this crisis is not to ban AI (please don’t), nor to romanticise a pre-digital past. The challenge is to design learning environments where thinking remains central and where technology strengthens, rather than replaces, cognitive effort.

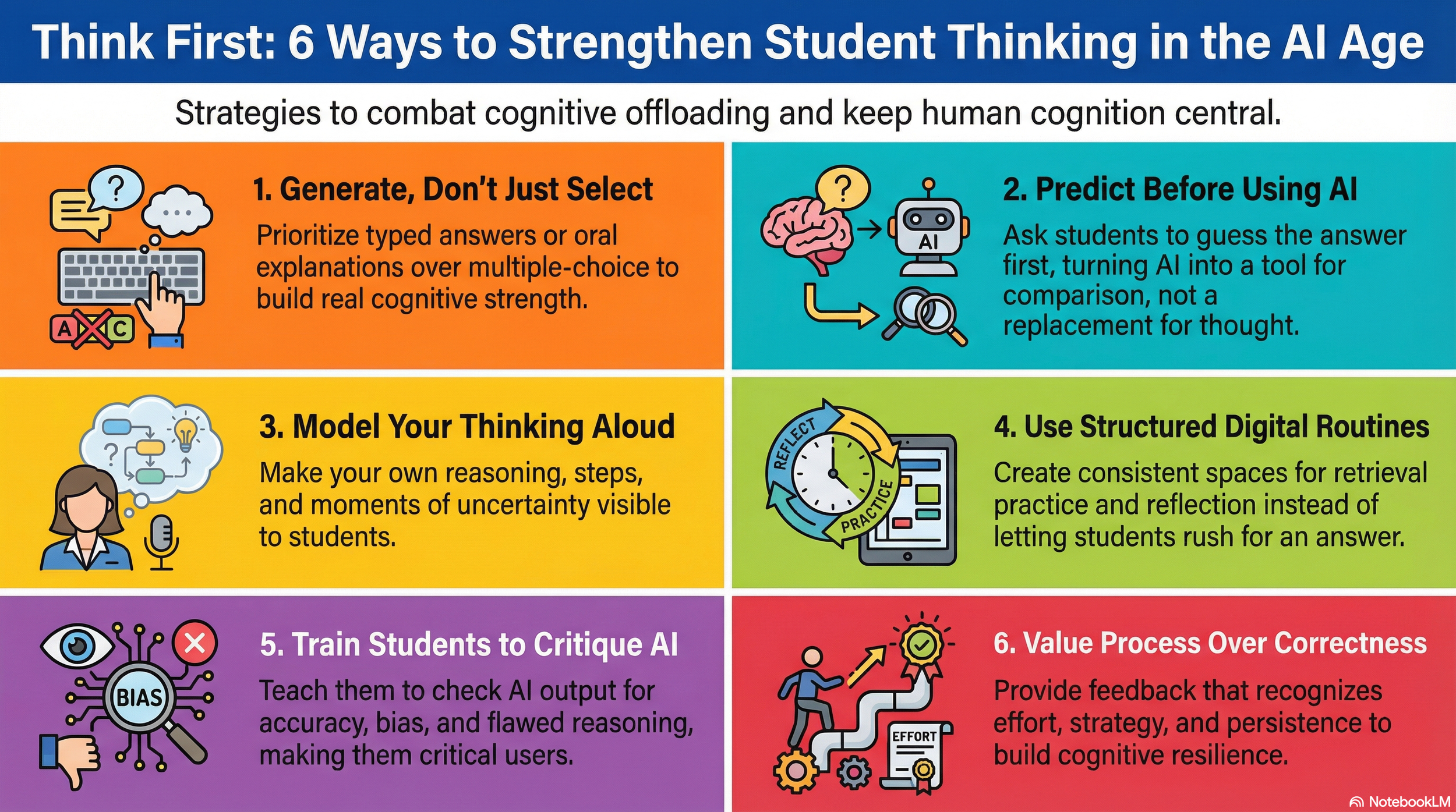

Strategies that have worked well in my experience include:

Prioritise generated responses over selected responses. Typed answers, oral explanations, and written reasoning build cognitive strength. Guessing does not.

Ask students to predict before using AI. Prediction activates prior knowledge. Then, AI becomes a tool for comparison, not a replacement for thought.

Model thinking processes explicitly. Explain reasoning aloud. Show the steps. Highlight moments of uncertainty.

Use structured digital routines (such as Class Notebook), I have used it for many years because it creates consistency, space for retrieval practice, and opportunities for reflection instead of rushing.

Train students to evaluate AI output critically. Accuracy, bias, reasoning, and coherence must be checked. AI becomes a partner for metacognition.

Provide feedback that values process over correctness. Feedback that recognises effort, strategy, and persistence builds neural resilience.

These practices protect the cognitive processes that AI often bypasses.

The Future of Human Learning

If schools want to prepare children for an AI-shaped future, our responsibility is not to make learning easier, but to make thinking stronger. Digital transformation must be anchored in pedagogy, not novelty. Teachers need training in cognition, memory, and attention, alongside their training in technology. Parents must understand the difference between getting the answer and knowing the answer. Leaders must design routines that protect the cognitive effort children need.

AI will evolve. Our commitment to thinking must remain constant.

AI may change how we write, communicate, and work, but it will never be able to replace the human struggle that makes learning meaningful. If we want children to grow into capable, reflective, independent thinkers, we must guide them to use AI with intention.

Cognitive offloading is not the enemy. Unconscious offloading is.

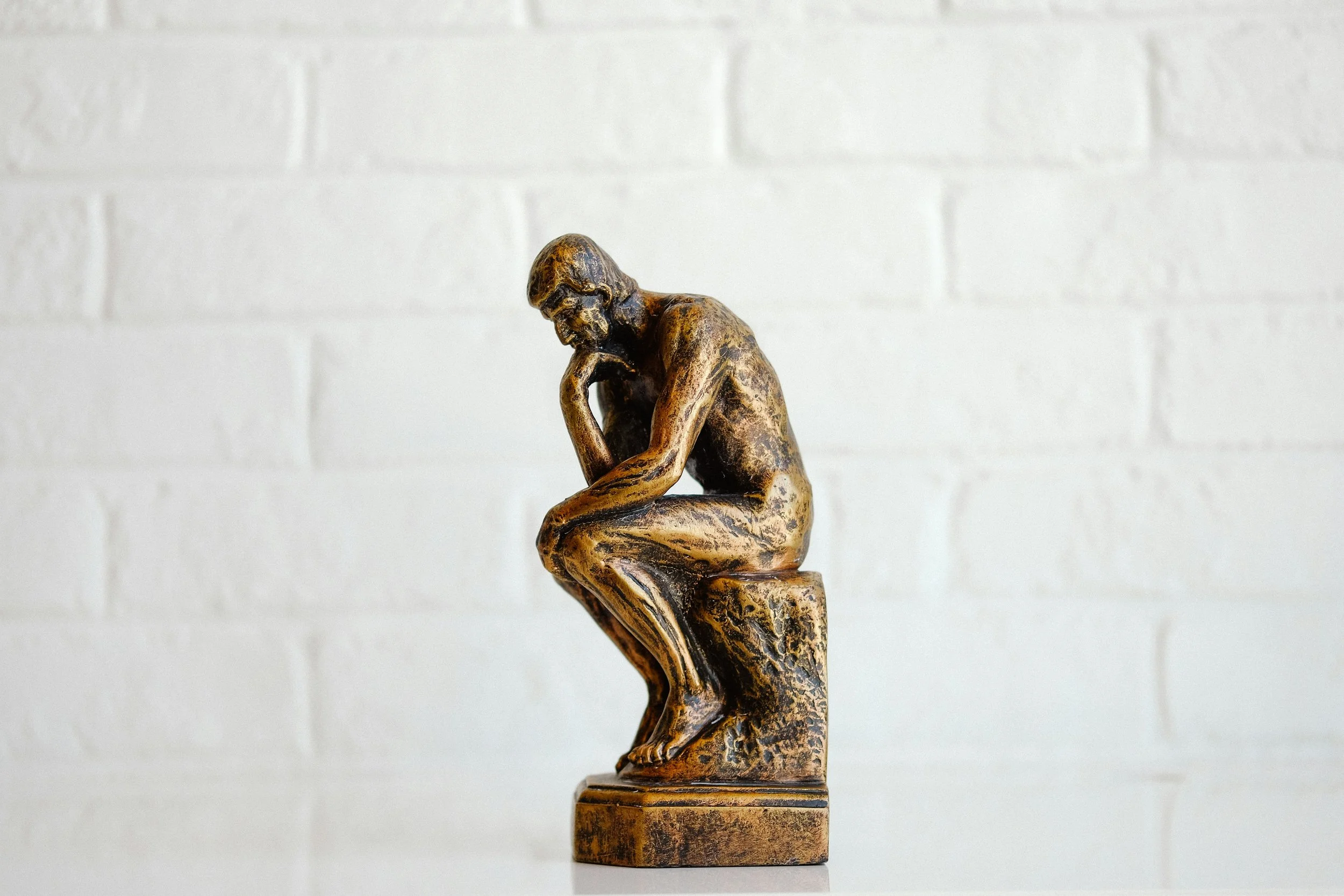

Our role as educators is to protect the moments when a learner pauses, considers, and says,

“Let me think first.”

About the Author

Miguel Haro Torres is an educator and digital learning leader passionate about helping schools use technology in ways that strengthen, rather than replace, thinking. He has spent more than ten years supporting teachers and students in developing deep learning habits, combining cognitive science with meaningful digital practice. His work focuses on pedagogical design and building school cultures where thinking remains at the centre of learning.